One if the few bonuses of the 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown in the UK was the dramatic reduction of aircraft noise around our homes. Certainly in the Southeast of England, it gave us some thought as to the number of aircraft in the sky, and what the consequences might be if something went wrong…

Aviation in the UK is split between what is known as Commercial Airport Transport (CAT) and General Aviation (GA). The CAT sector operates out of 25 airports and accounts for around 900 aircraft. However, the GA sector accounts for 15,000 aircraft, flown by 32,000 pilots, operating out of 125 aerodromes licensed by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and over 1,000 other flying sites (According to the General Aviation Awareness Council – our mapping data suggested 1650 sites) (1,2).

Roughly 96% of the aircraft in the UK are engaged in General Aviation, engaged in business, leisure engineering and training activities, and HM Government estimate that the sector employs around 38,000 people (3).

Each licensed airfield has its own firefighting response, termed airport rescue and firefighting services (RFFS) governed by the CAA guidelines and they are required to be:-

- .. proportionate to the aircraft operations and other activities taking place at the aerodrome;

- Provide for the coordination of appropriate organizations to respond to an emergency at the aerodrome or in its surroundings;

- Contain procedures for testing the adequacy of the plan, and for reviewing the results in order to improve its effectiveness.

(CAA 2020)

Ensuring Adequate firefighter training

So simply put, each airfield needs to ensure it has adequate training, media, personnel in appropriate quantities to deal with any likely incident, given its size and traffic.

There are around 1654 airfields in the UK, with 125 of those being licensed

However, this is only limited to licensed airfields and the response is typically limited to the airfield itself, and the immediate surrounding area. Airfield vehicles are often specialist aviation firefighting vehicles – not necessarily suitable for driving potentially long distances to an incident. Even so, it is a well-established principle that RRFS would only fight the initial stages of any fire, to be relieved by, and with command passed to local authority fire services.

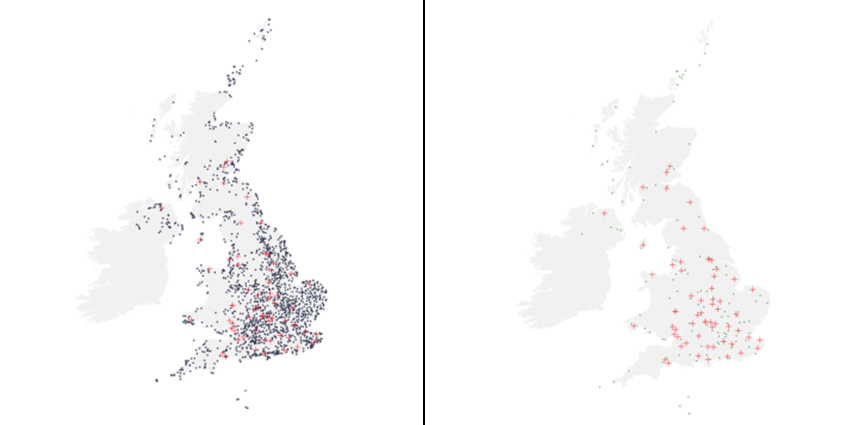

There are around 1654 airfields in the UK, with 125 of those being licensed. In 2019-2020 (to date) there have been 62 air crashes, of which 9 involved a fatality. If we plot the locations of all airfields of any type, all the licensed airfields and the crashes, we can see the spatial relationship between them. Below, we see the two distributions – on the left, crashes versus all airfields and on the right crashes versus licensed fields.

It’s clear that the crosses (crashes) and dots (fields) are not always in the same place, so clearly there is a potential problem here – namely the specialized airfield fire response is unlikely to be able to respond. Using the spatial analytical capability of QGIS, the open-source GIS software, we can then start to look at the distances from the airfields of the crashes.

We can see that (based on the 2019-2020 data) that on average a crash occurs 3.22km from an airfield, but 15.78km from a licensed airfield (where the firefighting teams are). The maximum distance from a licensed airfield was 57.41km, two thirds of the crashes were more than 10km from a licensed airfield and over a third were more than 18km away.

|

| Fig 1a (left) shows crashes versus all airfields. Fig 1b (right) shows crashes versus licensed airfields only. |

Aircraft incidents pose complex firefighting challenges

So, what does this all mean? Well the simple conclusion we can draw from this data is that there is a sizable risk of an aircrash occurring on the grounds of a non-airport fire service.

In 2019-2020 there have been 62 air crashes, of which 9 involved a fatality

Bearing that in mind, it’s also worth considering that aircraft incidents pose challenges to firefighters and firefighting, that need to be considered. The construction of aircraft has been evolving since the first days of flight, with materials that are strong, light and cheap to produce being adopted and in recent years created to order.

This has seen a move from natural materials, such as wood and canvas towards aluminum and man-made materials, and in recent years man made mineral fibres (MMMFs) which are lighter and stronger than natural materials, and can be moulded into any shape. The problem is, MMMFs disintegrate into minuscule fibres when subject to impact or fire, which can stick like tiny needles into firefighters’ skin, leading to skin conditions, and pose a significant risk to respiratory systems if breathed in.

As with all fires, there are risks associated with smoke products, with exposure to fuels and other chemicals and so there is the potential for a widespread hazmat incident, with respiratory and contamination hazards. Finally, there is always the risk, more so perhaps with military aircraft, of explosives or dangerous cargoes on the aircraft that put firefighters at risk.

The problem is therefore this: There is a constant, but small, chance of an aviation incident occurring away from an airport, and requiring local authority fire services to act as the initial response agency, rather than a relieving agency. These incidents, when they do occur, are likely to be unfamiliar to responding crews, yet also present risks that need to be addressed.

PLANE Thinking

Despite this landscape of complex risk and inconsistent response coverage non-airfield fire services can still create an effective response structure in the event of an aviation incident away from an airfield. We have drawn up a simple, 5-step aide-memoire for structuring a response, following the acronym PLANE (Plan, Learn, Adapt, Nurture, Evolve).

We are aware that all brigades will do this already to some extent (in fact they are obliged to). We are also aware that there was little point going into the technical details of firefighting itself – that is handled elsewhere and in far more detail – but instead we considered a broad, high-level system to act as a quick sanity check on the response measures already in place.

There is always the risk, more so perhaps with military aircraft, of explosives or dangerous cargoes on the aircraft that put firefighters at risk

In many ways this mirrors existing operational risk exercises, and begins with a planning process – considering the nature of risk in the response area, building links with other agencies and operators, and collating and analyzing intelligence. Services should expand their levels of knowledge (Learn) around the issue, and consider appointing tactical advisors for aviation incidents and using exercises and training programs to test and enhance response.

Having identified the risk landscape, and invested in intelligence about it, we may then need to consider adapting our approaches to make sure we are ready to respond, and having carried out all of this activity, we need to keep the momentum going, and continue to nurture those relationships, and that expertise cross the service.

Rapid technological advancement

Aviation technology does not stand still. Many of us will have seen this week the testing in the lake district of the emergency response jetpack (4), and this is just one example of the pace of technological advances in the sector. Consider the huge emerging market of UAVs, commercially and recreationally and the potential for incidents related to them, as well as their potential application in responses. Finally, Services, potentially through their dedicated TacAd roles, need to keep abreast of emerging technologies, and ensure that the Planning and Learning continues to match the risk.

Aviation technology does not stand still

So, in conclusion, we have a (very) simple system for preparing for the potential for airline incidents off airfields. We are happy to admit that it’s not going to solve all of every brigades’ problems, and we’d like to think it simply holds a mirror to existing activities. We do hope that it does give a bit of structure to the consideration a potentially complex process, and that it is of some use, if only as a talking point.

Best practices and technologies and will be among the topics discussed at the Aerial Firefighting Europe Conference, taking place in Nîmes, France on 27 – 28 April 2021. The biennial event provides a platform for over 600 international aerial firefighting professionals to discuss the ever-increasing challenges faced by the industry.

References

1. General Aviation Awareness Council. Fact Sheet 1 - What is General Aviation (GA)? 2008.

2. Anon. UK Airfields KML. google maps. 2020.

3. Davies B. General Aviation Strategic Network Recommendations. GA Champion, 2018.

4. Barbour S. Jet suit paramedic tested in the Lake District “could save lives.” BBC News. 2020.

Article Written by Chris Heywood and Dr Ian Greatbatch.